A Closer Look at Your Hips

by Lee Boyce, CPT on July 6, 2013July 2013: A Closer Look at Your Hips

In the movies, there’s always that character who’s in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The guy who gets the bad rap just for being there, and for being the easiest dude to blame for the heist.

In the case of the human body, the “bad guy” always ends up being the same link – the hip flexors. Too many times in the gym do I see trainers notice irregularities in compound movements, then, feeling like masterminds, proudly inform the client that the reason they can’t do it is because “they’ve got tight hip flexors”. Well, as I apologize in advance to be the bearer of bad news, many times the hip flexors aren’t the go-to site of the problem. See, one thing that’s become a theme of clients in the industry is that most people (with office jobs, cars, and couches at home) develop tightness in the hips which does contribute to other issues. However, with dysfunctions in major movements like squatting deadlifting, and the like, they become the easiest “fallback” to hold blame for problems during the movements. Let’s get to the bottom of this.

What ARE the “Hip Flexors”, and Let’s Talk Flexibility vs. Mobility

Most people refer to the hip flexors as two main groups – the iliacus muscles, and the psoas muscles. Truth be told, there are actually nine muscles that contribute to flexion at the hip, including the Sartorius, Piriformis, Rectus Femoris, Adductor Brevis, and TFL. Having said that, it’s not too fair that they always get blamed as the bad news bears. When it comes to hip flexor mobility, it’s important that we can establish the proper definition of mobility when compared to flexibility. Flexibility basically refers to the muscle’s capability to freely change in length (like an elastic band). Mobility has more to do with the integrity of the joint around which the muscles articulate. Having good mobility is the foundation for achieving good range of motion in exercises and is a product of proper length-tension muscle relationships around the body.

Signs of Immobility at the Hip

- Inability to disassociate femur from pelvic girdle and lumbar vertebrae

- Insufficient squatting depth

- Notable anterior pelvic tilting

Often times, you’ll notice compensations occur in the mechanics of the body when hip flexor mobility is an issue. For example, looking at a lifter’s gait when walking and running can be a major indicator. Are they rotating from the hip with every stride, or are the lumbar vertebrae working overtime to create rotation that shouldn’t exist in those segments? As mentioned above, this goes beyond simple inflexibility of the hip flexors, because it involves other muscles to create integrity and full ROM at the joint. Inflexible hip flexors would simply create poor hip extension, and that’s an easy fix.

The Fixes for Mobility Issues

Doing stretches to muscle groups isn’t bad – but it’s only half the battle if you want to truly achieve bigger ROM that lasts. In the case of the hip flexors, it’s especially important to know this based on just how many muscles contribute to the action of hip flexion. The first step is to focus on dynamic mobility drills. The femur (upper thigh bone) has to get used to moving around freely in its socket, and a static hip flexor stretch just won’t do that.

Cradle Walks – these help bring the femur into external rotation and double as active dynamic stretches for the glutes, adductors, and piriformis.

Spiderman Walks – serve as an active dynamic stretch for the quads, adductors, and iliacus muscles. Brings the femur into full extension at the hip joint also.

Leg Swings – the simplest way to get hip adduction and abduction ROM.

Focusing on these big three hip mobility drills will act as solid groundwork to get your hip joint in proper working order.

A Tissue Issue

Now it’s time to actually address “tightness” of the hip muscles. Too frequently static stretching is overprescribed, and as you’ve read above, a usual suspect to poor ROM is actually the mobility of the joint itself. As well, stretching muscles without them being in the proper tissue quality to actually “take” to the stretch is basically a wasted effort. Most of the intended stretch will be shifted towards the connective tissue rather than the muscle belly itself. It’s time to reintroduce a piece of equipment that doesn’t get enough love.

Foam Rolling – Buy a dense foam roller and work on all the tissue that surrounds the hip joint – the glutes, the TFL, the tissue surrounding the IT band, and the upper quads. Take your time as your roll over each region. If it feels perfectly fine, your roller isn’t dense enough – this shouldn’t be comfortable! To get at the iliacus and other common “hip flexors”, I recommend using a tee ball or lacrosse ball. It’ll help get into those smaller areas that a large roller just can’t hit. After rolling, stretch the snot out of your muscles. It’s the best time to focus on the muscles’ elasticity now that the tissue is in better quality and more malleable.

Tight AND Weak? Ain’t Nobody got Time for That!

Here’s another thing. Not enough people want to appreciate that muscles that are tight are also weak. Psychologically, it just seems like the two don’t go together. We associate “tight” with contraction, shortness, and the like, therefore we think the muscle is dominating or strong enough as it is. The truth is, poor tissue quality (and other muscles not helping out) can lead to the muscles in question taking on way more than they’re supposed to and even changing their role in the body. A perfect example is the TFL which can come in to act as a primary hip flexor when other muscles aren’t doing their job.

So what should the hip flexors be doing? In short, they should be helping to flex the hip, but they have to play their role as stabilizers too. Using the example of a squat, hip flexors to look most closely at are the psoas muscles. They’re responsible to hip angles smaller than 90 degrees – which means the bottom end range of a deep squat. In translation, a set of strong, responsive psoas muscles can actually help to pull a lifter down into a deeper below-parallel squat position. Hitting the psoas in exercise is limited, however, but sprinting and box jumping (onto a high enough box) will allow the knee to travel higher than most exercises in the weight room will, so this is what I’d recommend.

Strength and flexibility are equally as important as one another in basically every muscle group we train, and the hip muscles are no different.

Activations

Small movements can be used to get the hip flexion muscles out of their dormant state, and prepared to do work. Doing this is important to connect your mind to the muscles and ensure that you’re not using the wrong muscles to perform your big movements right off the bat. For the iliacus muscles, lie on your back and turn your toes outwards. Raise one straight leg up and diagonally outward (like you’re kicking a soccer ball with the inside of your foot) and make sure you only use your hip to raise it. Try to keep your toe and heel at the same level, and don’t let the heel fall towards the ground. Hold for 5 seconds. Return to the midline, and then repeat at ascending levels for 5 more seconds each.

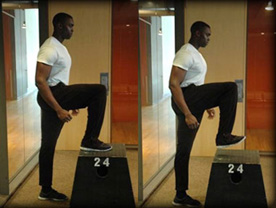

To work on the psoas, it’s just a matter of changing the degree of flexion. As mentioned before, the psoas kicks in to pull the knee up to a hip angle inside 90 degrees (or up closer into the chest). To activate it, find any box that goes roughly up to your knee level, or a height that would make your hip flex to 90 degrees when you step up to it. Stand tall and plant one flat foot on the box. Make sure your knee angle is inside 90 degrees also. Without twisting or compromising your body’s upright position, stay tall and pull your knee up off the box as high as possible. Hold for 5 seconds. This exercise is a real eye opener for people who have weak psoas muscles, so don’t be surprised if it’s very difficult at first.

A Few More Arbitrary Thoughts

When it comes to looking at the body holistically, it helps to think about our own personal body as a whole unit. We all know that there’s no single body in “perfect balance”. That said, it’s not necessary to stretch or strengthen both sides of the body completely evenly, as it will just encourage the same ratio of imbalance throughout the body. Where the hips are concerned, give stretching the hip flexor muscles more attention and the loosening up of glute and hamstring tissue less attention. The glutes and hamstrings are often viewed as tight (especially hamstrings), but their issues are usually resultant of restrictions elsewhere. Moreover, releasing the glutes and hamstrings with already short hip flexors can just encourage more forward momentum at the pelvis and further shortening at the hips, especially for those who are already quad-dominant, namely, everyone.

Hip Hop Hooray

The hips shouldn’t always be the bad guy on the scene. As we’ve seen, many things contribute to their deficiency, and it’s a good idea to look at their strength, mobility and flexibility separately and also as the y apply to your lifts. Taking this approach could be the key to getting those added inches of ROM in your squat, more stability through your trunk and core, or eliminating that nagging lower back pain that’s been plaguing your ability to do deadlifts. I’m sure you’ll find this info useful if you follow these tips for success!

Lee Boyce

Lee Boyce is based in Toronto, Canada, and works with strength training and preventive care clients. He is the owner of leeboycetraining.com and is a contributing author to many major publications including Musclemag, TNATION, Men’s Health, and Men’s Fitness. Check out his website www.leeboycetraining.com and be sure to follow him on twitter @coachleeboyce.